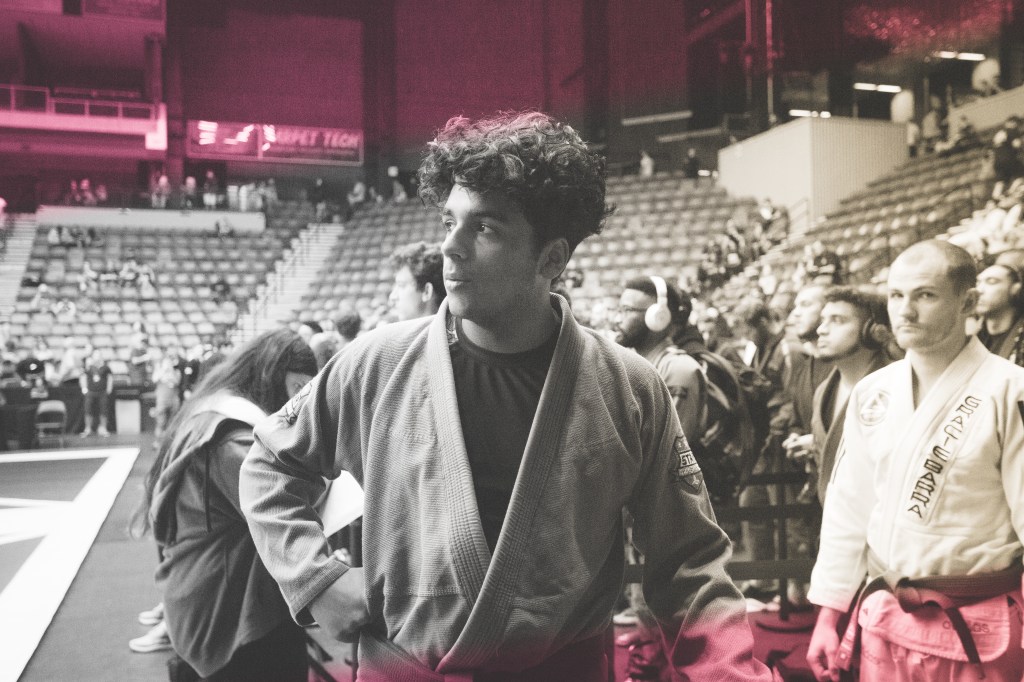

Title photo credits: Shane Kislack/ @shanekislackphotographs – instagram

The concept of the “fight or flight” response is deeply ingrained in our understanding of stress and has its roots in early psychological and physiological research. Walter Cannon, an early 20th-century American physiologist, pioneered the term “fight or flight” to describe the body’s instinctive response to perceived threats. Cannon’s work was fundamental to the recognition that when an organism encounters a threat, a complex physiological response is triggered, including the release of adrenaline, increased heart rate, heightened senses, and rapid breathing. This physiological response is all about facing the threat (“fighting”) or flee to safety (“flight”). This immediate response is a survival mechanism, allows the body to respond quickly to dangers in the surrounding environment. Building on Cannon’s work, Hans Selye, an endocrinologist, introduced the concept of general adaptation syndrome (GAS) in the 1930s. While Cannon focuses on immediate responses to stress, Selye explores the body’s longer-term responses. Selye’s GAS model describes three stages of stress response:

alarm, resistance and exhaustion. During the alarm phase, the body reacts similarly to Cannon’s “fight or flight” response. If the stressor persists, the body enters the resistance phase, where it tries to cope with the ongoing stress, often depleting its resources. If stress is prolonged, the body will eventually reach the exhaustion stage, which can lead to exhaustion, illness and even death. Together, Cannon and Selye’s work provided insight into the body’s multifaceted response to stress, laying the foundation for countless studies and advances in the field of stress research.

Over the summer I had competed in Jiu Jitsu and instead of correlating my EMT experiences to the History of medicine, I want to compare the history of medicine to one of my long time hobbies, Jiu Jitsu.

Stepping onto the mat at a large-scale Jiu Jitsu event is a combination of excitement, anticipation and nervousness. The crowd’s overwhelming energy, awareness of the stakes, and understanding of the need to face top opponents can instantly trigger a fight-or-flight response, reminiscent of the description of Walter Cannon on our body’s reactions to threats.The first fight brought on a rush of adrenaline, an elevated heart rate, and a heightened awareness of every movement and counter-movement, as if my body was ringing the my warning bell, preparing me for the challenge.However, once I got through this period, something transformative began to happen. by the second and third matches, the change was clearly visible. Drawing a parallel with Hans Selye’s general adaptation syndrome, my body and mind moved from an initial alarm reaction to the stage of resistance. Instead of being overwhelmed, I found myself adapting, understanding my opponent’s strategy, and perfecting my strategy with each subsequent battle. The roaring crowd began to fade to distant hums, my breathing became more rhythmic and a state of calm settled over me. By the time I faced my final opponent in the championship round, my system had internalized the stressors, and my cognitive and physiological responses worked together in harmony.. The highlight of this trip was not only winning the fight but also securing the coveted top spot for the American 195-pound title. The complex dance between the fight-or-flight response and GAS plays out in real time, demonstrating the profound capabilities of the human body and mind under pressure.

Leave a comment