This post is going to be part of a paper I wrote on Lubna of Cordoba, a scholar who transcribed over 500,000 pieces of work in math and sciences. I had the opportunity to visit Cordoba in May of 2023 and see the historical sites that Lubna herself walked around in. The class that I am taking in which this paper as submitted in is History of philosophy, science and medicine – which is the perfect course to take knowledge from and place it on this blog.

In the rich tapestry of historical scholarship, woman emerged as symbols of intellectual strength and resilience, direction, and brilliance in The fields of science, mathematics and astronomy are traditionally dominated by men. These women, separated both by time and geography, served as pillars of their respective times, overcoming social barriers, and pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Lubna of Cordoba, born a slave in 11th-century Spain, rose in the Umayyad court, not by birthright but by pure merit. According to Rabia Ismail, a Ph.D. a scholar of Jamia Millia Islamia, Lubna was not only a talented mathematician but also the woman behind a royal library with over 500,000 books. Ibn Bashkuwal, a respected source, praised her unparalleled expertise in writing, grammar, poetry and especially mathematics. According to Ibn Bashkuwal, no other individual in the Umayyad palace could match her intellectual capacity. Lubna’s story transcends her humble beginnings. After organizing the palace library, she quickly left an indelible mark, impressed the royal family, secured her freedom, and received the coveted title of “personal secretary”. Amid the library’s vast holdings, she and other women immersed themselves in a variety of fields, from calculus to languages, translating ancient manuscripts and writing poetic insights into life in the palace. Her legacy culminated in the library’s transformation into a coeducational institution, where she enthusiastically taught courses ranging from mathematics to philosophy. At the same time, figures such as Hypatia and Cecilia Payne demonstrated similar perseverance and genius in their times. Hypatia, revered for her contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy, shone brightly in Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries, while Cecilia Payne, several centuries later, did shattering glass ceilings in the world of science. Together, these women’s stories illustrate the profound importance of women’s contributions in fields that history often remembers as male-centered. Their story is a testament to the fact that intelligence and passion know no gender, and their legacy continues to inspire countless people, especially women, around the world.

Historiography, the study of historical texts, is crucial to understanding historical figures. especially when there is ambiguity surrounding their life stories. The way stories are recorded, interpreted, and disseminated can significantly influence our understanding and perception of historical figures, events, and movements. In the case of Lubna of Cordoba, a 10th-century intellectual power in Al-Andalus, historical recording becomes especially complicated. Like many women who have made significant contributions to science, mathematics and academia, her story is filled with gaps, disparities, and prejudices. This reflects a broader challenge in historical sources, especially regarding women in academia and science. Chronicles, written primarily by men in patriarchal societies, often underestimate, ignore, or inaccurately portray the contributions of women. The study of Lubna shows some such differences. Basic facts about her life, like the year of her birth, are not set in stone. Even her upbringing, whether she was born a slave or not, remains a matter of debate among historians. These discrepancies are not simple factual errors but symbolize the broader problem of women’s marginalization in the historical record. This quote from the Muslim Women’s Times Magazine eloquently summarizes these challenges. “It is hard to decipher the feminine truth of this legendary woman in a patriarchal reading of the world”. The author of the journal had suggested that Lubna may represent two female intellectuals merged into a single figure due to the inability of male historians to recognize multiple influential female figures in the same context is telling that. Such interpretations raise pertinent questions about how much of what we know about Lubna is fact and how much is the result of confusion, misinterpretation, or even historical erasure. “The legend of Lubna of Cordoba is a tale interwoven with facts and exaggerations.” This reflection emphasizes that while Lubna’s contributions to knowledge and culture were certainly significant, the story of her life that we inherit is the product of patriarchal narrations. The lament that “history is most often HIS story” is an impactful reminder that historical narratives are often filtered through male perspectives, marginalizing or distorting contributions and experiences of women. In the study of Lubna of Cordoba, as with many female historical figures, questioning, challenging, and delving into sources of information becomes important to gather a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of her life and her contributions. The historiography surrounding Lubna is not just an academic exercise; it is a mission to reclaim and honor the legacy of a remarkable woman in the chronicle of history.

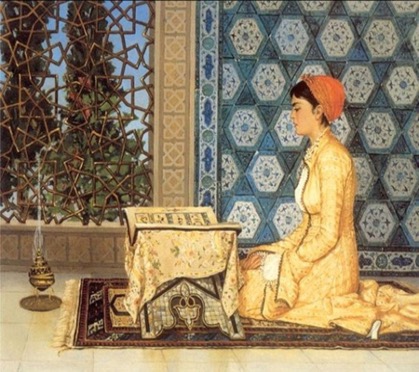

At the heart of medieval Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, more specifically Al-Andalus, emerged as the beacon of the Enlightenment during the golden age of knowledge. 10th-century Cordoba was not just a city but an intellectual center, where Muslims, Jews and Christians coexisted, weaving a rich tapestry of cultures, ideas, and cultures. diverse ideas and innovations. This dynamic environment has become fertile ground for scholars, philosophers, and mathematicians, fostering an environment where learning is respected, and knowledge is a valuable currency. Among the luminaries of this era was Lubna of Cordoba, a figure whose origins and journey are both inspiring and surprising. Some sources claim that Lubna was of Spanish descent and began life as a slave, but her remarkable intelligence and talent brought her to unprecedented heights in the Andalusian court. Her rise to prominence in the age of male supremacy is a testament to her exceptional abilities and the progressive environment of Al-Andalus. Lubna’s roles are many: an eloquent poet, a meticulous note-taker, a respected member of the royal court, and a passionate mathematician. Charged with being secretary and scribe to Sultan Abd Al-Rahman III and later his son, Hakam II, she had access to and later gained the authority of management for the Royal Library of Córdoba. This is not just an ordinary library; it is the crown jewel of its time, on par with other great stores of knowledge.

However, Lubna was not satisfied with simple guardianship. Sources indicate that she actively participated in enriching the library’s collection, making trips to countries as far away as Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad to purchase valuable manuscripts. Her role goes beyond simple transcription. She took on the difficult task of translating complex texts, including influential works by legendary figures such as Euclid and Archimedes. Additionally, she enriches these texts with her annotations, integrating her ideas and interpretations. But perhaps what makes Lubna different is her altruistic spirit. Beyond the confines of palaces and libraries, she believed in the democratization of knowledge. While wandering the streets of Cordoba, she took it upon herself to educate local children, whether it was helping them recite math or challenging them with equations. She embodies the essence of the intellectual philosophy of Al-Andalus, believing in the power of knowledge to elevate, empower, and unite.

Leave a comment